Reliability Data for ImPACT

This chapter includes technical and psychometric information on ImPACT Version 4, including details on the reliability of the modules, and the various forms of validity evidence that have been established. All data presented here are for the current online version of ImPACT. In addition, there is substantial reliability and validity data presented on the company website at www.impacttest.com.

Over the years, there have been a sizeable body of literature that has documented the reliability of ImPACT. In general, ImPACT has been found to be highly reliable across time. As the items of the test and the six modules have not changed, this literature is relevant to ImPACT Version 4.

Test-retest reliability#

Multiple studies have evaluated the reliability of ImPACT across two time intervals. In a study of collegiate athletes by Schatz (2010) the reliability of the ImPACT test battery over time was investigated. The author studied 95 athletes completing baseline cognitive testing at two time periods, approximately 2 years apart. No participant sustained a concussion between assessments. All athletes completed the ImPACT test battery; dependent measures were the composite scores and total symptom scale score. Intraclass correlation coefficient estimates for visual memory (.65), processing speed (.74), and reaction time (.68) composite scores reflected stability over the 2-year period, with the greatest variability occurring in verbal memory (.46) and symptom scale (.43) scores. Using RCIs and regression-based methods, only a small percentage of participants' scores showed reliable or "significant" change on the composite scores (0%-6%), or symptom scale scores (5%-10%). These results suggest that college athletes' cognitive performance at baseline remains considerably stable over a 2-year period.

In a follow up study, Schatz and Ferris (2013) evaluated the reliability of the ImPACT test battery over a shorter time span. Two ImPACT tests were administered with 4 weeks between assessments. Participants had not previously completed ImPACT and had no history of concussion. Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) and intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) were as follows:

Verbal Memory = .66/.79 (r/ICC), Visual Memory = .43/.60, Visual Motor Speed = .78/.88, Reaction Time = .63/.77, and Total Symptoms = .75/.81. Dependent sample t-tests revealed significant improvement on only Visual Motor Speed Composite Scores. Reliable Change Indices showed a significant number of participants fell outside 80% and 95% confidence intervals for only Visual Motor Speed scores (but no other indices), whereas all scores were within 80% and 95% confidence intervals using regression-based measures. Results suggest that repeated exposure to the ImPACT test may result in significant improvements in the physical mechanics of how college students interact with the test (e.g., performance on Visual Motor Speed), but repeated exposure across 1 month does not result in practice effects in memory performance or reaction time.

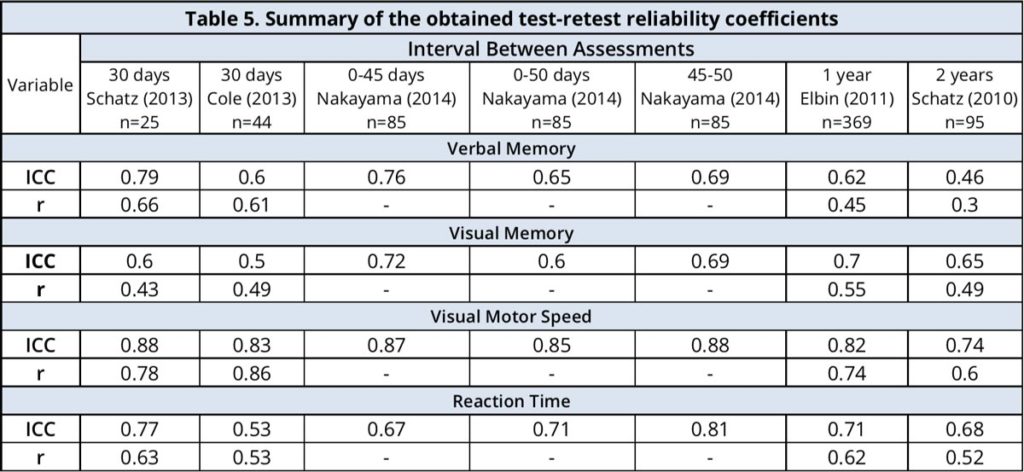

Most recently, (Nakayama et al.) in a 2014 study of 85 college age students, concluded that ImPACT is a reliable neurocognitive test battery at 45 and 50 days after the baseline assessment. These findings support those of other reliability studies that have reported acceptable intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) across 30-day to 1-year testing intervals, and they support the utility of the ImPACT’s use in a multidisciplinary approach to concussion management.

Other research has produced similar findings. A summary of the findings is presented in Table 5.

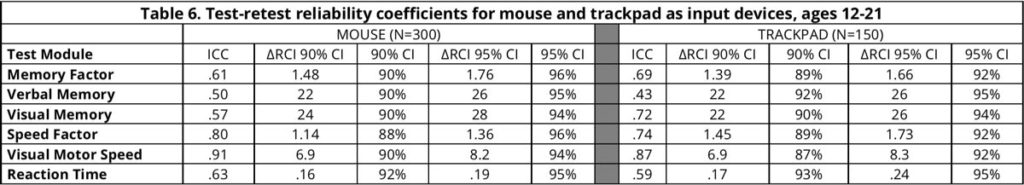

As part of the research to establish the reliability of ImPACT Version 4 we calculated test-retest reliability on a sample of test-takers ages 12-21. This age group was selected because these are the ages where retesting is likely done on a regular basis as part of the test taker’s participation in organized group activities such as sports teams or a school. Test takers were 300 individuals from the standardization sample who completed two baseline assessments using a mouse input and 150 individuals who completed two baseline assessments using a trackpad input. Test-takers that utilized a computer mouse were 166 males (55.3%, mean age 16.2, SD=2.2 years) and 134 females (44.7%, mean age 15.7, SD=2.3 years). Test-takers that utilized a track pad were 74 males (49.3%, mean age 16.1, SD=2.2 years) and 76 females (50.7%, mean age 15.8, SD=2.2 years). All test-takers completed an initial baseline assessment, and a second baseline with a between test interval ranging of 7 to 14 days

(mean=10.1 days, SD=2.4 days). Test-retest reliability was calculated using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the ImPACT Composite Scores as well as Two Factor Scores.

Using RCIs, only a small percentage of participants' scores showed reliable or "significant" change on the composite scores (0%-3%), or factor scores (1%-3%). These results suggest that test-takers cognitive performance at baseline remains considerably stable over a 2-week period, for both mouse and trackpad input (Table 6).

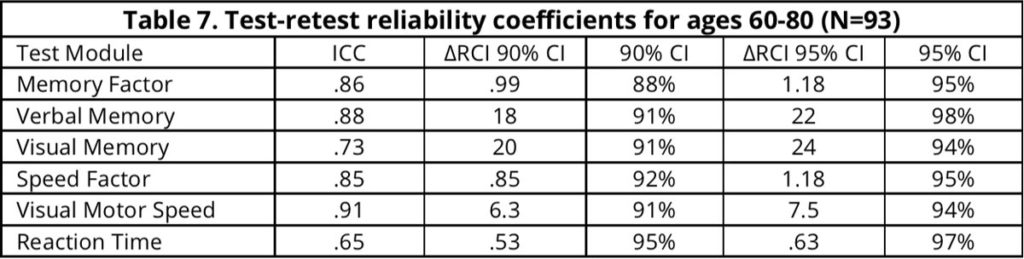

A second set of participants ages 60-80 (mean age of 68.18, SD=5.1 years) completed two ImPACT assessments across an average range of 30 days

(mean=16.04 days, S.D. = 8.65 days). The sample consisted of a total of 93 individuals (64.5% females, 35.5% males). Intraclass Correlations (ICCs) were calculated to examine test-retest reliability for the component tests across the time periods (See Table 7).

Using RCIs, only a small percentage of participants' scores showed reliable or "significant" change on the composite scores (0%-1%), or factor scores (0%-2%). These results suggest that test-takers cognitive performance at baseline remains considerably stable over a one-month period (Table 7).

Not the solution you are looking for?

Please check other articles or open a support ticket.